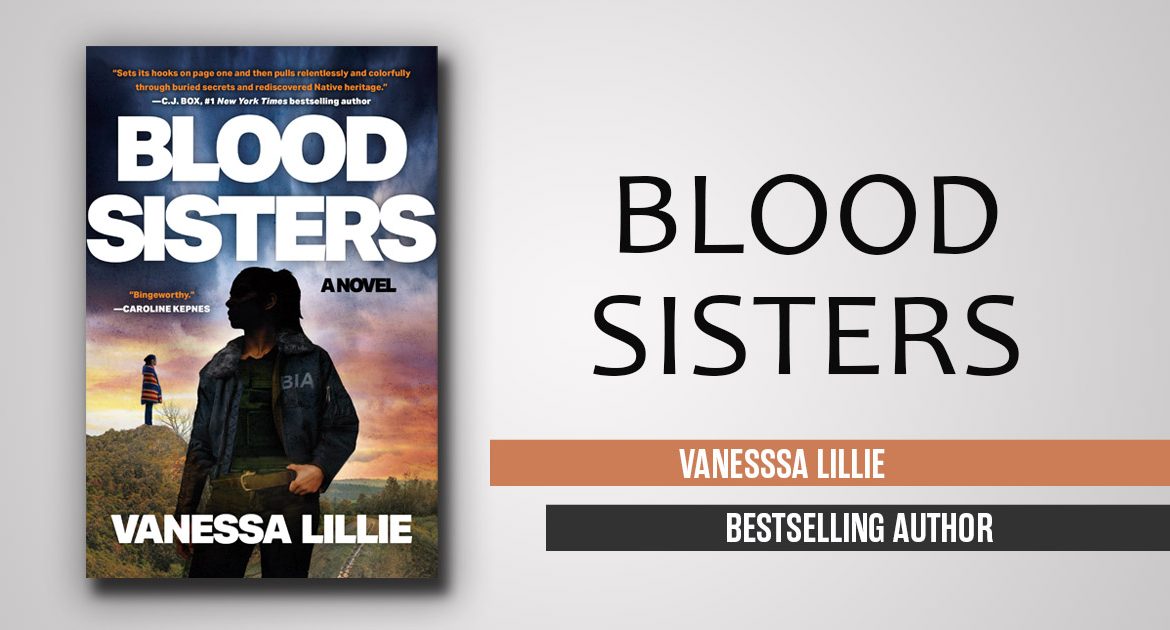

Vanessa Lillie is the bestselling author of the thrillers Little Voices, For the Best and coauthor of the Young Rich Widows series. Her forthcoming novel, Blood Sisters, launches a new suspense series and releases October 31, 2023

AGILVGI (SISTER)

Picher, Oklahoma

May 8, 1993

A devil kicks in the front door, but he’s holding a pistol instead of a pitchfork. The three of us girls, watching TV in a tangle of relaxed limbs on the floor, grab one another and scream.

“Tsgilis!” I call out the name of Cherokee evil spirits from stories around campfires meant to scare us, as a real one fills the narrow doorway. His white plastic mask and horns glow with all that dark night behind him. He stomps his nasty boots into the small trailer with a thud-thud, thud-thud.

A second devil follows on the metal stairs. The trailer creaks like a roller coaster to hell. Syd clings to my arm as tight as when we play Indian rope burn with the boys at school.

“Sister, are they raven mockers?” Syd hisses, referring to the soul-stealing Cherokee witches older cousins told us about.

“Them are dollar-store masks.” My voice shakes though I try to sound tough. “Ain’t no witch wearing that.”

The two white Tsgilis are not long and lean, but thick like tree stumps. I wonder if the real devil wears a shiny vest or prom tuxedo. No way he looks like these two in their sweat-stained shirts tight across their beer bellies.

Terror triggers a baptism over my body. A flood of helplessness spreads from my chest and washes down to my curled toes. It’s a feeling of smallness only those who live nowhere with nothing understand.

The moment stretches and their horned plastic masks catch the light in the wobbling ceiling fan. Pale blue eyes focus on us. I swear the frozen grins on the masks curl.

“You girls stay put,” yells the first devil. He stabs a fat finger at where we’re trembling in the center of the living room. The other devil beside him barely lifts his mask to spit chew on the ratty carpet.

My heart thumps in my ears, but I try not to let on. I’m pretty sure these kinda men are like wild dogs, surviving on meanness and the smell of fear.

“Where’s your daddy?” the second devil hisses at me like he hasn’t already scared us bad enough.

Our gazes whip around at one another like tether balls. Syd always insisted we’re old enough to be alone, even out in the middle of nowhere. I can handle it. I’d never let anything hurt you.

The truth is out here, out nowhere, no one can be saved.

The only sound in the trailer is cheesy laughs from Full House on the TV. We stay quiet except for muffled sobs. Usually at least one of us can comfort the other when something goes wrong. Not tonight. Maybe not ever again.

We scoot closer together until our arms are around each other. Skin to skin, warm and familiar. We bow our heads like we’re asking for forgiveness at the pastor’s altar call.

There is a click and the devil aims his pistol right at the center of where we’re clinging to one another. “You girls don’t got no voice now? Yapping usually, ain’t ya?”

I glare at that devil and see his eyes flash blue. I realize he’s stared at me before. Watched me, even, from high up in the trees along the fence line. This devil is a hunter, just like Tsgilis.

“Now, listen here,” the first devil calls. “Tell us where your daddy keeps his money from that skunk weed he’s been selling.”

Only canned laughter from the TV breaks the silence.

“We can make you talk,” the other devil barks. “Or we can make you beg.” He aims his gun and fires right at the screen. I’ve heard shots ring out plenty, but in this small room, the sound is a piercing explosion like a firework gone wrong.

We shiver and sob but don’t say shit.

The devil with the gun lunges at us. “Have it your way.” He jams the pistol inches from my face. “Start with the pretty one. That’ll teach her daddy.” Then he points the gun at Syd. “Put this one that looks like a boy in a closet. I’ll tie that one up.”

We scream for one another, arms outstretched, as we’re ripped apart.

“Luna!”

“Syd!”

“Emma Lou!”

Syd tries to kick the devil who’s grabbed her under the arms. She stops fighting quicker than I’d ever expect. She’s supposed to protect us. To save us when we step wrong. But then I see why she lost her fight. The devil is dragging Syd to the tiny storage closet by the kitchen. She knows what I know: there’s a loaded shotgun in there.

I’m flipped hard onto my stomach, and my face is shoved into the carpet by a nasty boot.

I pull away, but the hard toe connects with my jaw. Fresh pain blooms as I squeeze my eyes shut and try to slow my breathing. To stop shivering. To not give these wild dogs what they want.

Play possum, that’s what we do in the middle of nowhere to survive.

Play dead until Sister saves us from the devils.

I go completely still except for a prayer on my lips, whispering to a god who’s never answered out here, out nowhere, Let Agilvgi send the Tsgilis back to hell.

Chapter 1

Exeter, Rhode Island

Fifteen years later

Tuesday, May 6, 2008

I brush wet dirt from the skull’s damaged eye socket and wonder if my sister is dead.

The thought is an old habit. Normally, I barely notice, the fear is like a clear film that floats past my eye to be blinked away and forgotten.

Footsteps crunch to draw me away from worries about my only sister, Emma Lou, in rural Oklahoma. My focus returns to this hilltop near the Sandy Brook hiking loop in Rhode Island. Where I stand is not an area for hikers. I am on Narragansett Native land, which means I need to hurry to preserve the scene from whoever is headed this way.

I drop the toothbrush caked in mud and hustle to my backpack. I open the bag as I hear the snap of someone moving past the yellow caution tape I used to lock down the site yesterday evening.

Grabbing a soft cotton sheet from my bag, I fling it into the air to cover the entire skeleton I excavated from the earth this morning. An air pocket floats beneath the sheet as if the bones are trying to rise and leave the shallow grave.

I narrow my eyes to see who’s coming over the hill. I half wave, relieved, at the sight of a familiar too-thin face with neat brown hair. He’s in his usual loose jeans and starched yellow polo with a tribal seal stitched on the pocket.

“You pretty far along, Syd?” asks Ellis Reed, the Narragansett tribal historic preservation officer I work with the most. “Coroner won’t like it.”

“They’re short-staffed and sending an intern.” I don’t hide my annoyance as I toss him a can of bug spray. “Starting before dawn means some college kid won’t screw up our chances of an ID on the remains.” I pause and decide to stick to this half-truth. Sharing that I’m in hurry and meeting my wife in a couple of hours for an appointment will only lead to more questions.

“Kutaputush,” Ellis says thanks in Narragansett then coats himself with a thick layer of spray. These damp woods will have mosquitoes already out for blood. He tosses the can onto the ground and then crosses his arms as he stares down at what brought us here. “Appreciate the sheet.”

Not that I need to explain as much to Ellis, but it should be common practice to cover remains. To treat the dead with respect and not as a spectacle. Especially bones like these, uncovered by accident, because they were never meant to be found.

“Can I take a look?” he asks.

“I didn’t wait. I’m almost done,” I warn as I retie my short black hair at the nape of my neck.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, says I shouldn’t have excavated until Ellis, as the tribal representative, and coroner showed. But my new boss works from the BIA headquarters, one thousand miles away, and from what I’ve heard about her, she wouldn’t let an intern screw up her dig site either. Not that I asked.

I lift the sheet straight into the air and ball the fabric into my arms with a sniff of the fancy detergent my wife likes. She was softly snoring this morning when I gave up on sleep and came back here with my headlamp and excavation equipment. After two days of finding nothing of significance in my geological survey of the area, I was shocked to strike bone. With the last rays of sunlight at my back, I made the call to Ellis.

He blows out a long breath. “I’m glad you found her.”

I nod once and follow his gaze to where I’ve brushed away the layers of earth around the delicate bones still wearing a dirty white dress. The arms and legs are fanned out like she was making a snow angel.

I’m lucky to work with Ellis because he treats me with respect, something the BIA hasn’t traditionally given to tribal leaders like him. He could see me as just the BIA, the oldest bureau in the government. Created by the Department of War to exterminate Native people, culture, and ways of life across this “new” country “discovered” by men like Columbus and colonized by pilgrims and founding fathers, despite the tens of thousands of years of Native life that preceded them.

The modern charge of the BIA is different, of course, but the bad blood rightfully remains. The culture at the BIA is changing so there are more of us who see our job in a new way, especially since it’s personal to me. I’ve never shared this with Ellis, but I’m Native, too. Cherokee from Oklahoma out here on Narragansett land in Rhode Island. But I look white, and I refuse to be the white woman who brings up her Cherokee heritage when it’s convenient. Selectively dropping it into a conversation with people who live Native life every day.

As a new generation in the agency—and Native myself—I do my best to make inroads with tribes and show that I’m here to help, not harm. But there’s three hundred years of terrible history that tells another story.

I also greatly respect Ellis as a tribal leader who must live in two worlds. The need to preserve the past but also continue building the tribe’s future through what’s allowed by the government. He must find some version of balance between what the tribe needs to continue existing—language, land base, culture, medicine—and what the government will agree to give.

My role as an archeologist is simpler. I see myself as a midwife to the past for the future. To support the tribes by advocating for what they need to continue traditions that honor their thousands of years of history as they carry this knowledge into the future.

“Syd? Did you hear me?”

“Sorry.”

He clears his throat. “Small cranium size.”

I focus back on the bones between us. “Even without the dress, the narrow ridges of the eyebrows suggest female to me.”

He crouches near the feet. “What’s the stratigraphy?”

I almost grin at his question, which shows his knowledge extends well beyond what’s needed for his job title. It’s something I immediately respected in him when we first met after I took this job five years ago. I like to think he appreciates it in me, too. Neither of us is a fan of the status quo, especially not when it comes to justice.

“The same layer of earth,” I say. “Two feet four inches deep, except the skull and feet were three inches higher on each side.”

“Shallow grave dug fast,” he says with a sigh. “What do you make of the skull fracture?”