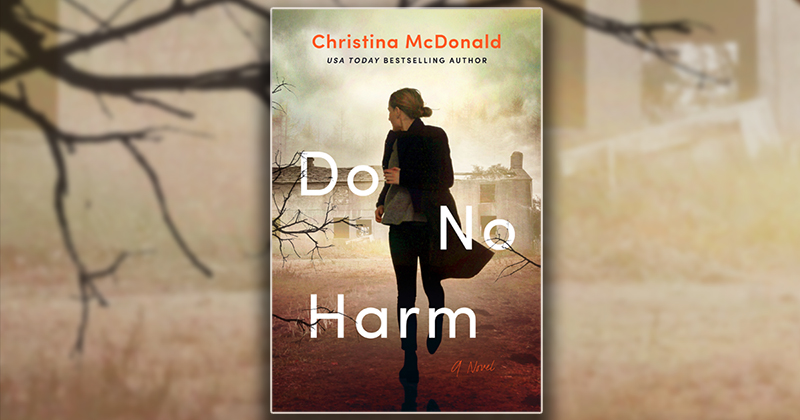

From the USA Today bestselling author of Behind Every Lie and The Night Olivia Fell comes an unforgettable novel about the lengths one woman will go to save her son.

Even good people

Emma loves her life. She’s the mother to a precocious kindergartener, married to her soulmate—a loyal and loving detective—and has a rewarding career as a doctor at the local hospital.

But everything comes crashing down when her son, Josh, is diagnosed with a rare form of cancer.

Get addicted to bad things

Determined to save Josh, Emma makes the risky decision to sell opioids to fund the life-saving treatment he needs. But when somebody ends up dead, a lethal game of cat and mouse ensues, her own husband leading the chase. With her son’s life hanging in the balance, Emma is dragged into the dark world of drugs, lies, and murder. Will the truth catch up to her before she can save Josh?

A timely and moving exploration of a town gripped by the opioid epidemic, and featuring Christina McDonald’s signature “complex, emotionally intense” (Publishers Weekly) prose, Do No Harm examines whether the ends ever justify the means…even for a desperate mother.

Read the free excerpt below and Mark As Want To Read on Goodreads for chances to win advance copies!

Do No Harm

By: Christina McDonald

Coming Feb 16, 2021

Prologue

The knife burrowed into my side with a moist thwump.

I looked down, confused. The blade was buried so deep that the hand holding it was pressed almost flat against my stomach. My pulse hammered against the steel.

And then I felt the fire. My mouth dropped open. The blood was rushing out of me too fast, I knew, soaking my shirt, turning it from white to red in seconds. It was too late. Too late to save myself.

I looked into those familiar eyes, mouthed a single word.

You.

The knife slid out of me, a sickening, wet sound. Blood pooled at the bottom of my throat. And then I fell, an abrupt, uninterrupted drop.

I blinked, my brain softening, dulling. Images clicked by, one by one.

Polished black shoes.

The blur of snow as it tumbled past the open door.

The two-by-fours standing against the wall.

My body felt like it was composed of nothing but air. I had failed.

Chapter 3

Tuesday dawned gray and damp. A soft fall rain had settled outside, making the clinic look tired and dirty. Sagging chairs leaned against murky beige walls. A garbage can overflowed with empty paper cups. Wet jackets were hung on the coatrack, dripping onto the grimy linoleum. Reception was a crush of damp bodies that smelled of urine and feet and unwashed hair.

Some of my patients were from the eastern side of Skamania, where the yards were cut into neat squares of green, the bushes professionally trimmed. But most were poverty-stricken, immigrants, homeless, addicts, or all of the above. They had little or no access to health insurance, suffering agonizing pain instead of seeing a doctor because they couldn’t afford it. These were the people I’d gone to medical school to help.

The more cynical accused us at the clinic of having a savior complex, but I knew we were making a difference in these people’s lives. We were helping.

______

The more cynical accused us at the clinic of having a savior complex, but I knew we were making a difference in these people’s lives. We were helping.

______

I yawned as I walked toward the shared medical staff office. It had been a busy morning examining patients, doing wellness checkups, checking X-rays and lab results. And all on very little sleep. Josh had come into our bedroom too many times to count last night. When we’d first woken this morning, his fever had been too high to send him to school, so I’d called Nate’s mother and she’d agreed to stay with him. Fortunately, I was good on very little sleep. It was sort of a prerequisite to being a doctor.

I dug my cell phone out of the closet where I stashed my purse. Nate had texted me an X. I smiled and shot an X back to him, loving that he thought about me during his day. I then dialed Moira before my next appointment.

“Hello, Emma.” Moira’s voice was brisk, the tone she always used with me. I could hear the pursed-mouth exhale of the cigarette she thought nobody knew about. I imagined her draped in her cashmere and pearls, slate-gray hair smoothed perfectly into place, a cigarette dangling out the window in secret. I gritted my teeth but kept quiet. It wasn’t like we had a lot of choice of babysitters.

“Hi, Moira. How’s Josh?”

“He’s sleeping now. I gave him some ibuprofen.”

“If he wakes up—”

“I’ve raised four children, and I stayed home with all of them.

I know how to take care of a sick child.”

I swallowed a sharp retort, resenting the insinuation that I was a lesser mother than her because I worked. I tried hard to be grateful for my mother-in-law. She was a wonderful grandma to Josh, and she and Nate were very close. I just didn’t understand why she didn’t like me.

“Sure, of course. Sorry, um . . .”

Julia, a nurse practitioner I’d become friends with, tapped me on the shoulder. “Sorry!” she whispered when she saw I was on the phone. She held a cup of black coffee out to me. “Your four o’clock is in room four.”

Thank you! I mouthed. “Sorry, Moira, I’ve gotta run. Tell Josh I love him.”

I grabbed the coffee and swallowed a giant gulp before hurrying to the exam room. I scanned the patient’s chart as I walked. She was a new patient. Fifty-four years old. Normal temperature. Slightly elevated BP. I rapped gently on the exam room door and entered.

“Mrs. Jones?”

“Yes.” Alice Jones was small and frail. Her pale hair was threaded with gray and tied into a messy ponytail. Spiderweb wrinkles framed the corners of brown eyes clouded with pain. Her clothes were threadbare, a faded sweatshirt over ripped jeans, scuffed canvas tennis shoes with no socks.

Her husband, or who I assumed was her husband, sat next to her, a short, burly-chested man with shiny red cheeks, oily dark gray hair, and a pair of round glasses on a bulbous nose.

“Her back’s hurting,” he said, his voice too loud in the small space. “It’s been going on a long time now. It’s from all that damned gardening.”

I sat at my desk and turned to Alice. “I’m so sorry to hear that. I like gardening too. I have a whole freezer of vegetables I grew this summer. It’s pretty tough on our back and knees, though, isn’t it?”

I opened Alice’s patient file on my computer and typed notes as her husband explained her symptoms.

“I need to examine you now, Alice. Can you show me where the pain is?”

Alice struggled to stand, her husband holding her elbow firmly. She bent forward at the hips and touched a hand to her lower back.

“Sometimes my legs go a little numb,” she whispered.

I felt a heavy tug of pity in my stomach, the kind you’d feel for an injured bird. I examined her spine, assessed her ability to sit, stand, and walk. There was no redness or obvious swelling. The erector spinae muscles were smooth and strong, her reflexes normal. She wasn’t moving with enough pain to indicate a tear in the disc or enough restriction to indicate sciatica. But the numbness concerned me.

Doctors are scientists who work in an uncertain world. We use statistics, odds, and probability to diagnose and treat. Good or bad, we make the best-informed decisions we can.

______

Doctors are scientists who work in an uncertain world. We use statistics, odds, and probability to diagnose and treat. Good or bad, we make the best-informed decisions we can.

______

“I’m going to order an MRI.” I typed more notes in her file.

“Can you give me something for the pain?” she asked. “I’ve heard OxyContin is good for back pain.”

I kept my face neutral. The opioid crisis had made it difficult for doctors to know where the line was, when to prescribe pain medicine and when not to. It was a doctor’s job to help people, to assuage their pain, and yet I’d watched other doctors’ patients succumb to addiction. I knew about addiction firsthand, from my brother. I refused to let my patients become another statistic.

“I’ll write a prescription for naproxen to help the pain.” I smiled gently at Alice. “Once we get the MRI results, we’ll know better how to treat it. In the meantime, ice it, and stay off your feet for the next few days, okay?”

I handed Alice a leaflet with advice on how to treat back pain, gave her arm a compassionate squeeze, and left to see my next patient.

After my last patient of the day had left, I went to find Julia. She was clearing up after a pelvic exam in one of the exam rooms. Tendrils of dark hair were falling out of her ponytail. Julia was conventionally pretty, with sea-glass eyes and a slight overbite that somehow made her look even more adorable. She smiled faintly, and I noticed her wrist was bandaged, her movements slow, a little delicate.

“You all right?” I nodded at her wrist.

“Oh, carpal tunnel syndrome. Lucky me.” She laughed wryly. Julia was lively and cheery, a nurse practitioner who somehow did more work than all the doctors combined.

I told her about Alice Jones, and she scowled, her freckled nose crinkling. “The husband was here last week. Said he’d sprained his wrist.”

“He wasn’t wearing a wrist wrap.”

“I think Dr. Watson saw him. She might’ve prescribed some OxyContin, although check his chart to be sure. Maybe he was back for more? I seem to remember he was pretty aggressive. She was glad to see the back of him, I know that.”

I’d come across my fair share of angry men in the ER during my residency at Harborview in Seattle. I could still remember stitching open wounds with shaking hands, dodging drunken fists, standing near the exit to make sure I had a quick escape route.

I pulled a fresh sheet of medical exam paper over the table while Julia swiped the edges with an antibacterial wipe. We headed down the hall to the staff office. The rectangular area was bisected by a long desk with multiple charging points; on one side was a wall of cupboard space, and on the other a coffee-making station. Dr. Wallington was writing reports into a file while two of the other doctors were speaking earnestly about a patient. I pulled my coat out of the closet and turned to Julia.

“I’m glad I didn’t prescribe any Oxy, then.”

I’d learned that what healed wasn’t always in a doctor’s drugs or a surgeon’s blade. Sometimes it was the quieter things, like compassion, being heard and shown you mattered. I was confident I’d made the right decision with Alice. We’d wait and see what her MRI said.

______

I’d learned that what healed wasn’t always in a doctor’s drugs or a surgeon’s blade. Sometimes it was the quieter things, like compassion, being heard and shown you mattered.

______

“It’s a tough call these days,” Julia agreed. She lowered her voice and glanced around. “Speaking of Oxy, watch out for Marjorie. She’s on the warpath right now.”

Marjorie was the medical administrator of the clinic, which was situated within the auspices of Cascade Regional Hospital. She’d worked here forever and was unnecessarily crotchety as a result. I’d only worked here for three years, after taking over for a doctor who’d decided to partially retire, so she basically scared the crap out of me.

“What’s wrong now?”

“People keep leaving the medical supply room unlocked. She keeps all the samples from our pharma reps in there.”

“Yikes. I’ll keep an eye out.”

“Hey, wanna grab a drink?” Julia slid her coat on. “It’s happy hour. We can get one of those derby thingies you like.”

I laughed. Sometimes I was still surprised by the collegial nature of my job. “It’s a Brown Derby. Wish I could, but Josh has been sick. Rain check?”

Her reply was cut off as our receptionist, Brittany, burst through the door, her eyes almost comically wide.

“Dr. Sweeney! You need to get downstairs! Josh’s been admitted to the ER!”